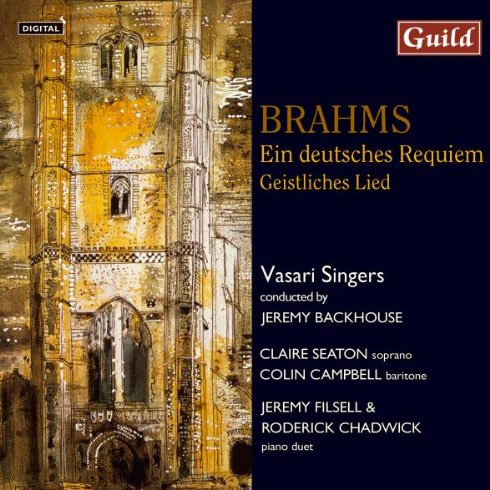

Share Album

- Run Time: 64.39

- Release Date: 2006

- Label: Guild

- ASIN: B000EMG6YI

Brahms: German Requiem (ein Deutsches Requiem)

£7.50

Delivery is charged at current Royal Mail prices. FREE on all orders over £30.00.Dispatched within 2-4 days of purchase.

- Chorus “Selig sind, die da leid tragen” 8.19

- Chorus “Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras” 12.51

- Solo Baritone & Chorus “Herr, lerre doch mich” 8.16

- Chorus “Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen, Herr Zeboath” 4.35

- Solo soprano & chorus “Ihr habt nun Trauigkeit” 6.25

- Solo baritone & chorus “Denn wir haben keine bleibende Statt” 9.41

- Chorus “Selig sind die Toten, die in dem Herrn sterben” 9.25

- Geistliches Lied, Op 30 4.36

Reviews

- Brahms: German Requiem (ein Deutsches Requiem) – Church Music Quarterly - Three ticks – essential listening, Warmly recommended.

The Vasari Singers have a velvet tone that is wonderfully suited to Brahms’s Ein deutsches Requiem. Their performance of the lovely chorus ‘wie lieblich sind deine wohnungen’ (known to many English-singing choirs as ‘how lovely are thy dwellings fair’) exemplifies the Vasaris’ command of line and phrase, and their broad dynamic range. Soloists Claire Seaton and Colin Campbell are excellent in their roles; and the piano duet accompaniment (Brahms’s own arrangement of the orchestral score) is executed with great sensitivity by Jeremy Filsell and Roderick Chadwick. Indeed, the attain the highest musical success of a piano duet partnership@ they sound like one musician (albeit a super-human one).

On the Vasari disc, Brahms’s Requiem is coupled with Geistliches Lied Op. 30: the same work as begins a CD by St Albans Cathedral Choir. It is interesting to compare a performance by a mixed adult choir accompanied by piano duet, with one by a cathedral choir of men and boys accompanied by organ. The Vasari Singers takes more than a minute less over the piece than the choir of St Albans Cathedral. While the acoustics of the recording venues and the different accompanying instruments are doubtless significant factors in the tempi, the two conductors view the work from slightly different angles. Jeremy Backhouse achieves a passionate intensity, while Andrew Lucas’s interpretation is a touch more serene. Although their German is clearly pronounced, both the Vasari Singers and the Choir of St Albans Cathedral never sound anything other than fine English choirs.

Church Music Quarterly

- Brahms: German Requiem (ein Deutsches Requiem) – musicomh.com - "...this recording is certainly worthy of a place alongside the numerous other versions of Brahms’ choral masterpiece."

When searching through the abundant and ever-multiplying marketplace of classical music recordings, one’s interest is easily piqued by an offering that seems somewhat out of the ordinary.

The latest disc presented by the highly versatile and successful Vasari Singers, featuring Brahms’ Ein deutsches Requiem and Geistliches Lied Op. 30, arouses such curiosity before it has even reached the CD player.

Fascination here resides in the decision to record the requiem with Brahms’ own piano-duet reduction of the orchestra score. Considering that the Vasari Singers are a relatively small group that might struggle to cope with full-blown symphonic forces, it makes sense to travel down the piano accompaniment route for such a substantial work. Nevertheless, one might yet be inclined to question the validity of such an endeavour. In his booklet notes, David Bray explains that this arrangement places a greater emphasis on the composer’s skilful choral writing while removing the elements of an “endurance test” present in the original version.

There is certainly an element of ease about the Vasari Singers’ performance under the competent guidance of Jeremy Backhouse. Their sound production is always controlled and well-measured, never strained or forced when the music becomes excited. Most importantly, one can definitely sense a significant shift in attention towards the choir as the accompaniment seems to take more of a back seat, allowing the listener to focus on a wonderfully lucid choral performance. One is struck in the opening „Selig sind, die da Leid tragen” by the superb array of tonal complexion as the choir captures the emotions of this deeply profound work. This zealous understanding of Brahms’ writing never wavers, permeating all aspects of the rendition. All the vocal lines are audible, even in tutti passages, and are sung with equally outstanding sincerity. Similar qualities are also apparent in the Geistliches Lied Op. 30, provided as a short yet pleasant bonus track after the requiem.

Of course, the orchestral version of Brahms’ requiem (or, for that matter, of any large-scale choral work) tests the stamina not only of the performers but also, when recorded, of the speakers through which the music is heard. Even if one is fortunate enough to possess a lavish sound system, the sheer size and weight of such considerable instrumental and vocal forces can be simply overwhelming. These were, after all, initially intended to be heard in the church or concert hall as opposed to the living room. By employing a piano reduction of the orchestral score along with a small choral ensemble, thus creating what is effectively a “chamber requiem”, the work gains an extra ounce of clarity which, in the context of a recording, often translates into an enhanced listening experience (though sometimes at the expense of the sustained intensity provided by symphonic proportions).

Jeremy Filsell and Roderick Chadwick are extremely convincing at the keyboard, doing their utmost to provide a full range of orchestral colouring (very much in the Lisztian vein of pianism). The haunting poignancy at the start of Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras is especially atmospheric, creating an ideal ambience for the choir’s chilling entry. In stark contrast, the forceful tutti sections are played with sheer brilliance and pizzazz, none more so than the startling central passage that accompanies verses 54b-55 of 1 Corinthians 15 in Denn wir haben keine bleibende Statt. Though occasionally one might wish that the pianists exercise a greater degree of artistic licence with regards to rubato, this is not a pervasive shortcoming, and on the whole the playing is quite enthralling.

Reference must be made to the soloists, both of whom are admirable in their delivery of Brahms’ sumptuous vocal lines. Baritone Colin Campbell is the more persuasive of the two. His silky-smooth voice and focused vibrato are exceedingly easy on the ear, and he performs his solo sections in Nos. 3 and 6 with passionate conviction. Claire Seaton’s account of Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit contains some equally thrilling moments. Though her crescendi occasionally sound somewhat devisal, she nevertheless possesses a glorious tone throughout, particularly in the higher portions of her register.

This CD is perhaps better-suited to the connoisseur, the person who already boasts a reasonable knowledge of Ein deutches Requiem in its orchestral form. Just as the first-time listener would benefit greatly from listening to the adeptness of Brahms’ symphonic writing, those more familiar with the work who are seeking to discover something new stand to gain the most from the alternative approach presented here. Make no mistake, however: far from being a gimmick, this recording is certainly worthy of a place alongside the numerous other versions of Brahms’ choral masterpiece.

William Norris

musicomh.com - Brahms: German Requiem (ein Deutsches Requiem) – The Singer - The Vasari Singers offer a sensitive reading of this work.

Using a piano duet arrangement made by Brahms himself, the Vasari Singers have released Ein Deutsches Requiem with Guild (GMCD 7302), which they recorded in St Jude’s in Hampstead. In some senses the piano accompaniment (Jeremy Filsell and Roderick Chadwick) gives and added reflective layer to the work and gives emphasis to the collective humanity of the text as sung by the choir. Soloists Claire Seaton and Colin Campbell join conductor Jeremy Backhouse, with The Vasari Singers offering a sensitive reading of this work, although sounding somewhat stretched at the higher reaches of increased tempo passages.

Antonia Couling

The Singer - Brahms: German Requiem (ein Deutsches Requiem) – Classic FM Magazine - ****

One of the earliest British performances of Brahms’ Requiem in 1871 took place in a private house in London. For reasons of lack of space Brahms provided a transcription of the orchestral accompaniment for piano duet, and that is the version performed here by the chamber-sized Vasari Singers. There’s an undeniable loss of dramatic splendour at the climax of the second movement (For all flesh is as grass), but the greater degree of intimacy is highly appealing. The choir makes a pure, well-blended sound, Claire Seaton is ethereally beautiful in the fifth movement solo, and Jeremy Backhouse holds it all together wonderfully well.

Warwick Thompson

Classic FM Magazine - Brahms: German Requiem (ein Deutsches Requiem) – Muso Magazine - The expression is beautiful and the dynamics precise.

Apart from being a musically luscious work, Brahms’ German Requiem changed the way choral music worked. Perhaps the greatest Romantic symphonic composer, Brahms used non-liturgical texts and a seven-movement form to create this stunning and often-recorded requiem.

Written in 1866 and inspired by the death of the composer’s good friend Robert Schumann, the work was first given a public airing in Bremen in 1868 and has become one of the most performed and recorded works in the religious repertoire.

Sometimes a choir is so good you can’t hear the individual voices. Unfortunately this often gives the feel of a Sibelius demonstration. Other times a choir is so bad all you can hear is one or two warbly sopranos. Somehow, the Vasari Singers seem to achieve a fine balance between the two, creating a rather ‘in the room’ Victorian choral sound.

The expression is beautiful and the dynamics precise. The piano is a little heavy-handed at times but soloists Claire Seaton and Colin Campbell are a joy to listen to. Seaton’s restrained soprano is well-suited to the gorgeous ihr Habt Nun Traurigkeit, whilst Campbell is suitably dramatic in Denn Wir Haben Keine Bleibende Statt.

This may not be one of the most polished versions of the Requiem but it’s certainly one of the more enjoyable ones. Vasari Singers – give up your day jobs!

Hazel Davis

Muso Magazine - Brahms: German Requiem (ein Deutsches Requiem) – BBC Radio 3 - I found it very moving to hear the work like this, shorn of its orchestral finery, but just as splendid in its nakedness.

“…a fascinating new disc on the Guild label, featuring a complete performance of the Requiem in its piano duet version, played by Jeremy Filsell and Roderick Chadwick, and sung by the Vasari Singers under Jeremy Backhouse.

It was this arrangement that was used in the English première of the work in 1871, which took place at the house of the distinguished surgeon Sir Henry Thompson.

Brahms intended his arrangement for people wishing to get to know the work at home, rather than for public performance – so I suppose it’s reasonable to ask what the point of recording it is, and I can only say that the proof of the pudding is in the hearing: it’s artistically perfectly viable and certainly doesn’t feel like a cheap imitation. Actually what it does do to the piece is very interesting. It effectively neutralises the orchestral part, and throws the weight onto the choral writing; and this makes you more aware of the abstract ‘stuff’ of the music itself. And I found it very moving to hear the work like this, shorn of its orchestral finery, but just as splendid in its nakedness.

On the whole the performance is good, though not really spectacular. The Vasaris’ sound is neat and rather light, which for my money isn’t quite what you want when you’re throwing the focus of such a massive work onto the choir. They do buckle under the strain in places, especially in those great fugues that just go on and on. And I’m not sure about the recording sound, which is muddy and piano-heavy. But these quibbles don’t ruin the performance, and the choir makes up for them by being very musical and extremely well-disciplined.

But I think special plaudits must go to the pianists, Filsell and Chadwick, who produce some beautiful colours, and some exciting muscular playing in the big orchestral tuttis. Overall then, a very interesting disc, and well worth considering, though don’t buy it instead of an orchestral version.”

James Weeks

BBC Radio 3