Share Album

- Run Time: 70.00

- Release Date: 2014

- Label: Naxos

- ASIN: B00NWZITG2

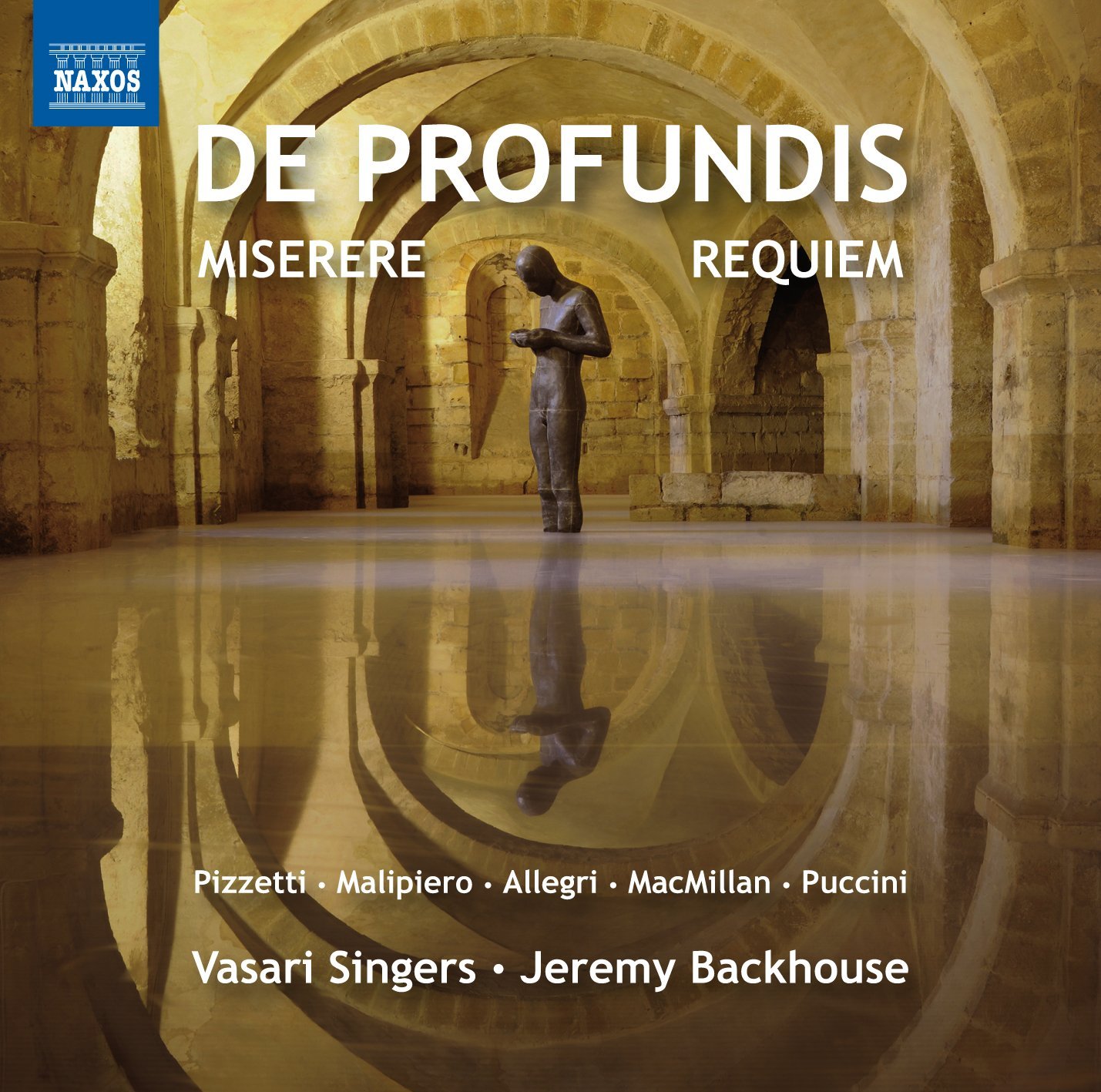

De Profundis, Miserere & Requiem

£7.50

Delivery is charged at current Royal Mail prices. FREE on all orders over £30.00.Dispatched within 2-4 days of purchase.

- De profundis Pizzetti 5.23

- De profundis Malipiero 4.34

- Miserere mei, Deus Allegri 13.27

- Miserere MacMillan 12.33

- Requiem for chorus, solo viola & organ Puccini 5.38

- Messa di Requiem Pizzetti 28.25

Album Details

These three pairs of sublime choral settings span well over 350 years. The earliest is Allegri’s Miserere, a work considered so precious it was kept secret until Mozart heard it and famously transcribed it from memory. James MacMillan’s 21st century companion piece is a transcendent reply to this challenge from history. Malipiero’s and Pizzetti’s resumption of a fractured friendship resulted in their mutually dedicated but differing settings of De profundis. Puccini’s brief but exquisite Requiem commemorated the death of Verdi, while Pizzetti, a late admirer of Puccini, revealed his empathy with vocal polyphony in a full setting of the Requiem Mass.

Reviews

- De Profundis, Miserere & Requiem – Gramophone - "...a strong sense of commitment to the sound that can surpass that of their full-time counterparts."

The thesis of this disc isn’t a new one but it is always a welcome approach and has been originally addressed. It couples two settings of three texts – the *De Profundis*, the *Miserere* and the Requiem – in contrasting pairs. The most startling contrast, surprisingly, does not involve the only non-Italian piece on the disc – James MacMillan’s *Miserere*, commissioned in 2009 by The Sixteen as a companion to the Allegri – but the two Requiems, which were written close to each other in time but differ so totally in outlook, both stylistically and in length, that they provide testament to the intelligence of the programming.

One of the most notable characteristics of such accomplished amateur choirs is that, although they can often lack the final polish of professional ensembles, there is nevertheless a strong sense of commitment to the sound that can surpass that of their full-time counterparts. And so it is here – the tuning is not always perfect and there are occasionally some standout voices (particularly from the back rows) that interfere with the blend – but that is ultimately forgivable solely on the basis that their corporate engagement with the music and the overall sound is so tangible in their performance. In the Italian pieces that can sometimes be at the expense of the breezy operatic sound that they really need; but the close recording of the full-choir passages supports a warm, broad sound that more than does an English style of justice to those Italianate pieces. And the audible corporate breathing in the choir that is particularly noticeable in the Allegri is (almost) silent testament to the greatness of English choirs.

Caroline Gill

Gramophone - De Profundis, Miserere & Requiem – Choir & Organ - Puccini’s accompanied five-minute setting of the Requiem is captivating.

Imaginative settings of the Requiem (Puccini and Pizzetti), *Miserere* (Allegri and MacMillan, the latter written in response to the former) and *De Profundis* (Pizzetti and Malipiero) are beautifully delivered on this CD. Pizzetti (d. 1968) has a tonal language evoking Bruckner; Malipiero (d. 1973) makes atmospheric use of organ and other instruments and a well-delivered baritone solo. The Allegri achieves a balance of warmth and space, and the necessary light touch. MacMillan’s powerful a cappella setting brings a new perspective to the text, the agile singing being a credit to the singers and to Backhouse’s lucid direction. Puccini’s accompanied five-minute setting of the Requiem is captivating.

Matthew Power

Choir & Organ - De Profundis, Miserere & Requiem – Musicweb International - Over the years I’ve heard quite a number of recordings by this choir and I’ve been consistently impressed. However, I fancy this disc may be just about the best thing they’ve ever done.

I’m sorry to say it but these days my heart usually sinks when I receive a disc that includes Allegri’s Miserere. I’m sure it’s an irrational and unfair prejudice on my part but I find the piece repetitive and it’s definitely over-exposed on CD. However, there are two reasons for making an exception here and welcoming its inclusion on this new disc by the Vasari Singers. The first is that it’s very well sung. The second is that’s it’s an integral part of an especially well thought-out programme. Jeremy Backhouse can be seen talking about the programme and the links between some of the works and composers by clicking here.

This is a programme of connections, one of which is the commissioning, by Harry Christophers and The Sixteen, of a setting of the Miserere by James MacMillan specifically to complement the Allegri setting. MacMillan succeeds brilliantly in fulfilling the request for his piece to be complementary and it’s very good to hear the two settings side by side, as here. Allegri uses three different choral strands in his setting: the full choir, plainchant verses sung by one or more male voices, and a distant semi-chorus. Some recent recordings I’ve heard opt to have the chanted passages sung by a lone male cantor and that works very well, providing extra contrast. Jeremy Backhouse adopts the more usual approach and has a group of men singing these verses: they do so with impressive unanimity. The semi-chorus is ideally distanced and very impressive they are. The top soprano ornaments some of the phrases. She does so tastefully and these decorations add variety. This is a very successful performance.

James MacMillan didn’t seek to replicate Allegri’s three-strand approach – wisely, I think; that would have risked pastiche. However, he does vary his choral textures most resourcefully during the setting. His piece is expertly imagined for the voices and the music is very responsive to the sentiments expressed in the text. I like very much the way that several times MacMillan writes passages that remind us of Allegri’s setting – yet he writes these sections without compromising his own compositional voice. This is a fine homage to the earlier setting and the Vasari Singers do it very well indeed.

The Allegri and MacMillan pieces are linked, albeit across the centuries. There’s a link also – and one that is much closer in time – between the pieces by Pizzetti and Malipiero that open the programme. They had been good friends but had fallen out – the fault lay with Pizzetti, it seems. In 1937 they patched up their quarrel and, as a gesture of reconciliation, they agreed both of them would write a setting of the De Profundis, each dedicating his piece to the other. Malipiero composed his eloquent setting for a solo baritone accompanied by viola and piano. In this performance an organ is used instead of a piano and, quite honestly, I find it hard to imagine that a piano would be preferable, given the nature of the music and the organ’s sustaining power. Here the baritone is Matthew Wood, a member of the Vasari Singers. He’s very impressive; his voice is well-focused and pleasing in tone and his diction is admirably clear. I enjoyed listening to him very much and the husky tone of Jon Thorne’s viola makes a very attractive addition to the texture. The other interesting feature of the accompaniment is an optional part for bass drum. It’s a very discreet part but Daniel Burges, a member of the choir, gauges the part perfectly so that it adds an unexpected colouring to the piece without intruding.

Pizzetti’s setting, for which he uses a shorter and somewhat different version of the text, is for seven-part unaccompanied choir. It’s very beautiful and Jeremy Backhouse and his singers do it full justice. We should divert for a moment from Pizzetti’s music to consider the small piece by Puccini, which I don’t recall hearing before. It was composed in 1905 to mark the fourth anniversary of the death of Verdi. It’s for chorus accompanied by viola and organ. The viola adds a plangent tone to the texture, which is most effective. It’s a short and largely unassuming piece and, in a programme of links, it merits its place because the second time the piece was heard was at a 1924 memorial service for Puccini at which Pizzetti delivered the eulogy.

It’s Pizzetti who provides the most substantial work on this disc in the shape of his 1922 Requiem for unaccompanied choir. This very beautiful piece is something of a rarity in performance though it’s been recorded at least once before. That recording is a superb Hyperion version by the Choir of Westminster Cathedral and James O’Donnell, made as long ago as 1997 (CDA67017). I don’t see that Hyperion disc as a competitor to this new Naxos recording; rather, the two CDs are complementary. One reason is that the programmes differ: The Westminster Choir, who also include Pizzetti’s De Profundis, offer music by Frank Martin as the remainder of their programme. The other, more important factor is that the two choirs offer very different – and equally valid – listening experiences. The Westminster choir is all-male with trebles on the top-line and they’re recorded in the spacious acoustic of Westminster Cathedral. So by listening to them and to the Vasari Singers we can get two nicely contrasting views of Pizzetti’s eloquent Requiem.

There is a pronounced flavour of plainchant in the music and that’s evident right from the start of the Introit. From the basses’ chant-like opening phrases the music soon flowers into lovely polyphony, which is beautifully sung here, the sopranos radiant. There’s a full setting of the Dies Irae and the tone of a lot of the music may come as a surprise. The opening, which is again chant-inspired, is very subdued, basses and altos singing the text while the tenors and sopranos float wordless melismas over the melody. These melismatic phrases recur several times during this movement, which is by some distance the longest in the work. There are several impassioned outbursts when the words justify such treatment but the prevailing mood is that of a prayer for forgiveness. The concluding lines, ‘Pie Jesu Domine, dona eis requiem. Amen’, are set to the most gentle music imaginable. This deeply affecting though brief passage is tenderly sung.

Pizzetti divides his choir into three four-part groups – one female, two male – for the Sanctus. This is memorable, the complex textures creating a ‘buzz’ of sound. The ‘Hosannas’ are ecstatic. The music for the Agnus Dei is texturally much simpler; it’s a gently prayerful setting which the Vasaris sing with great sensitivity. Unlike, say, Fauré or Duruflé, Pizzetti chooses to end not with a setting of In Paradisum but with Libera me. This predominantly dark text is marked to be sung ‘with profound fervour’. This is troubled, unsettled music though there is a serenely beautiful passage at the words ‘Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis.’ The very end of the work sets words about God judging the world by fire; a far cry, indeed, from the vision of the angels leading the departed soul into Paradise with which a number of Requiems conclude.

Pizzetti’s Requiem is a work of great beauty and sincerity and it deserves to be far better known than it is. This sensitive and expertly sung performance by the Vasari Singers can only help its cause.

Over the years I’ve heard quite a number of recordings by this choir and I’ve been consistently impressed. However, I fancy this disc may be just about the best thing they’ve ever done. A thoughtfully conceived and interesting programme has been flawlessly executed. The singing not only gives consistent pleasure but also prompts admiration. The recording has been produced by Adrian Peacock and engineered by Will Brown; they have achieved excellent results. Finally, Brenda Moore’s notes are very good indeed. I hope it will not be long before the next Vasari Singers disc and in the meantime I urge you to try this one, especially if you don’t know the Pizzetti Requiem – or even if you do.

John Quinn

Musicweb International - De Profundis, Miserere & Requiem – David’s Review Corner - Spanning over three hundred years, and largely written for sacred purposes, Vasari Singers offer a disc of unaccompanied choral works largely by Italian composers.

The disc turns the clock back to the 1630’s when Gregorio Allegri composed Miserere, one of the great masterpieces of his time for use in Rome’s Sistine Chapel. The work, one of beauty and ethereal tranquility, is here given a performance that goes to the top of my recommended recordings. Jumping forward to 1905, you might never put a composer’s name to Puccini’s brief Requiem, so untypical is the scoring. Likewise Pizzetti’s Requiem from 1922 could have come from fifty years earlier, the result being a very listener friendly-score, the most extended movement based on the famous Dies irae theme used by so many others, while the following Sanctus moves towards the ‘pop’ part of classical music. De Profundis stylistically turns the clock back even further to the days of the great polyphonic composers in its setting for seven part mixed voices. You will find it even more surprising that the modernist credentials of James MacMillan have been somewhat put aside in his use of the same text as Allegri’s Miserere. Completing this imaginatively programmed disc, Malipiero’s De Profundis is scored for baritone, viola, piano (here taken by the organ) and bass drum. The Vasari Singers are in fine voice for their conductor, Jeremy Backhouse; their dynamic range is wide, with quiet passages finely spun. First class sound.

David Denton

David’s Review Corner - De Profundis, Miserere & Requiem – The Classical Reviewer - De Profundis is a terrific new Naxos release of sacred choral works by Pizzetti, Malipiero, Allegri, MacMillan and Puccini beautifully sung by The Vasari Singers under their Director Jeremy Backhouse

Ildebrando Pizzetti (1880-1968) was born in Rome and studied at the Parma Conservatory before teaching in Florence, Milan and finally at the Academia di St Cecilia in Rome. In addition to operas, orchestral, chamber and instrumental works he wrote many choral works including the two featured on this disc.

The first of Pizzetti’s works on this disc is De Profundis (1937) which has a wonderful opening as the voices of the Vasari Singers slowly build the textures providing a fine rubato. Pizzetti layers the music especially well with a lovely passage where the female voices come in over the male voices, rising to a fine peak before falling back for the gentle coda.

Gian Francesco Malipiero (1882-1873) was born in Venice where he studied at the Licei Musicali before continuing his studies in Bologna. His study of the works of Monteverdi and the influence of Stravinsky, whose Rite of Spring he heard in Paris, remained influences on his music. His compositions covered most genres from opera through to piano music.

On this new disc we can hear the World Premiere recording of his De Profundis (1937). The work opens with deep pedal notes from the organ before a viola melody appears. Baritone, Matthew Wood is really fine when he enters in this melancholy setting. There are some especially lovely passages for viola and organ but it is the fine singing of Wood that makes this performance. The music rises centrally before, with deep organ, bass drum and viola the somewhat dark coda is reached.

Gregorio Allegri (1582-1652) is mainly known for the one work performed on this disc, his Miserere. Just as well-known is the story of Mozart writing down the work from memory whilst hearing it performed in Rome whilst visiting with his father, thus breaking the monopoly that the Vatican held on performances. Allegri was a singer and composer at the cathedrals of Fermo and Tivoli before becoming maestro di cappella of Spirito in Sassia, Rome as well as a singer in the Papal Choir.

Here the Vasari Singers bring a beautifully blended tone to the Miserere, beautifully poised with the female and tenor voices providing some lovely sections. Both Jocelyn Somerville and Susan Waton (sopranos) are credited in this work. Certainly the soprano taking the spectacularly difficult treble part, as it soars high up, is terrific. This is a very fine performance where subsequent passages are decorated and varied as indeed it is thought would have been the practice in Allegri’s time. The small group of singers that also includes Elizabeth Atkinson (alto) and Keith Long (bass) provide some beautifully decorated passages. The choir as a whole bring a very fine, mellow blend of voices that often have a mesmerising effect.

James MacMillan (b.1959) https://twitter.com/jamesmacm www.boosey.com/composer/james+macmillan was born in Ayrshire, Scotland and studied at Edinburgh University before undertaking further studies with John Casken at Durham University. His music is influenced by both his Catholic faith and Scottish folk music. Amongst his many compositions including opera, orchestral, chamber and piano works, sacred choral works hold a prominent place.

The Vasari Singers fine textures are particularly revealed in their performance of his Miserere (2009) with some very fine little rhythmic inflections and fine handling of MacMillan’s harmonies. When the music suddenly breaks out of its withdrawn calm there is singing of biting precision, the male voices showing fine incisive qualities. There are moments that are reminiscent of Allegri’s Miserere, the work intended to be a 21st century take on the setting of this penitential psalm. The music eventually rises suddenly for whole choir with moments of intense stasis over which the voices of Julia Smith (soprano), Julia Ridout (alto), Paul Robertson (tenor) and Matt Bernstein (bass) intone. The music rises finally for the whole choir in a moment of intense feeling before leading to the gentle coda. What a fine setting this is, receiving here a really lovely performance.

Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) is, of course, known as an operatic composer. He wrote a number of sacred choral works earlier in his career but his Requiem, written to commemorate the fourth anniversary of Verdi’s death, dates from 1905. As with Malipiero’s De Profundis, it is written for choir, viola and organ. It rises slowly and gently with a fine melody before the viola enters full of restrained emotion. The music soon rises more passionately but falls back as the viola adds an anxious feel. The choir, viola and organ lead to the sad coda with a simple amen and final organ chord.

The other work on this disc by Pizzetti is his Messa di Requiem (1922) a work given a higher profile with an award winning Hyperion recording by the Choir of Westminster Cathedral under James O’Donnell coupled with Frank Martin’s Mass for Double Choir.

The male voices open the Requiem before the female voices join, as this lovely setting moves forward. Jeremy Backhouse draws from his Singers a natural forward flow with little surges finely brought out. The Vasari Singers weave some lovely vocal textures and, towards the end some beautifully luminous singing.

The Dies Irae has a gentler opening yet with a nervous tension, this choir bringing a fine control with some beautifully woven musical lines. The music soon rises with singing of stunning brilliance and power. The old plainchant appears openly in a lovely passage. Lower and upper voices overlaid, rich lower textures and pure upper voices in a gloriously held section as we are led into the lovely coda.

There is a luminous opening to the Sanctus before it gains in richness. There is first rate singing here with so many textures emerging before rising to a central peak. At the end there is a very fine Hosanna in excelsis.

There is a gentle yet often soaring Agnus Dei with these voices providing a terrific blend of textures and a superb, deeply felt coda. The Libera me slowly rises to some powerful writing with some exceptionally fine choral work as the choir gently lead to the conclusion with some lovely rises in passion before the end.

Finely recorded in the excellent acoustic of Tonbridge School Chapel, Tonbridge, Kent, England, with excellent documentation and with full texts and English translations what more could one want. This is a terrific disc.

Bruce Reader

The Classical Reviewer